Physician Group Practice Trends: A Comprehensive Review

Bita Kash and Debra Tan

DOI10.4172/2471-9781.100008

Bita Kash* and Debra Tan

Texas A&M University Health Science Center, TAMU, Texas, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Bita Kash

Texas A&M University Health Science Center

TAMU, Texas-77843, USA

Tel: +979-436-462

E-mail: bakash@srph.tamhsc.edu

Received Date: February 03, 2016; Accepted Date: March 14, 2016; Published Date: March 21, 2016

Abstract

Physician group practices in the U.S. have grown and changed significantly in terms of health professional team composition, employment contract types, ownership type, size, and management in the last 20 years. In the past, physicians were largely selfemployed or part of small practices, however today's physicians are employed by large healthcare organizations, as well as integrated delivery systems.1 Between the years of 1996-1997 and 2004-2005, the proportion of physicians in solo and two-physician practices has decreased significantly from 40.7 percent to 32.5 percent.2 Today, most physicians work in the group practice setting in the United States. Moreover, physicians are increasingly practicing in mid-sized, single-specialty groups.

Keywords

Physician group; Trends

Introduction

Physician group practices in the U.S. have grown and changed significantly in terms of health professional team composition, employment contract types, ownership type, size, and management in the last 20 years. In the past, physicians were largely self-employed or part of small practices, however today’s physicians are employed by large healthcare organizations, as well as integrated delivery systems [1]. Between the years of 1996-1997 and 2004-2005, the proportion of physicians in solo and two-physician practices has decreased significantly from 40.7% to 32.5% [2]. Today, most physicians work in the group practice setting in the United States. Moreover, physicians are increasingly practicing in mid-sized, single-specialty groups [2]. Reasons behind the movement toward group practices, such as negotiating leverage, profitability, lifestyle, and improved quality of patient care, have been well documented in literature [3]. However, there is lack of information and clarity on what formally constitutes a group practice, as well as the standard definition of group practice size. It is important to understand the recent trends in medical group practice establishments and identify a typology for group practice size. Further, no study has yet to provide a comprehensive overview regarding group practice trends from the literature. In this comprehensive literature review, we assess the definitions of a medical group practice, describe recent group practice trends in the U.S., and offer a typology of group practice size. We also characterize market outlook and recommend next steps for future research focused on understanding and predicting medical group consolidation and mergers.

A Profile of Physician Group Practice

A recent survey in 2014 by The Physicians Foundation discovered that 53% of physicians described themselves as hospital or medical group employees, up from 44% in 2012, and 38% in 2008 [3]. Today, physicians are progressively joining hospitals or larger, consolidated medical groups [3]. Solo physician practices are declining; 17% of physician survey respondents reported they were in solo practices, in contrast to 25% in 2012 [3]. In addition, 45.5% of physicians cited single specialty practice to be the most common type of practice arrangement in 2012, a survey by the American Medical Association (AMA) [1]. Women physicians were reported to be less likely to work in single specialty groups in comparison to men physicians, 39.7% versus 48.0% respectively due to specialty choice [1]. These single specialty practices accounted for 57.3% of radiologists, 55.8% of anesthesiologists, and 52.7% of obstetricians/gynecologists [1]. In that same year, multi-specialty groups accounted for 22.1% where 36% accounted for internal medicine physicians, and 28.3% accounted for family practice physicians in multi-specialty groups [1] (Table 1).

Table 1: Distribution of physicians by ownership status and type of practice (2012)1

| Gender | Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership status | All | Women | Men | Under 40 | 40 to 54 | 55+ |

| Owner | 53.2% | 38.7% | 59.6%a | 43.3% | 51.4% a | 60.0% a |

| Employee | 41.8% | 55.7% | 35.8% a | 51.3% | 44.2% a | 34.7% a |

| Independent contractor | 5.0% | 5.7% | 4.7% | 5.4% | 4.5% | 5.3% |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Type of practice | ||||||

| Solo practice | 18.4% | 21.0% | 17.3% a | 10.0% | 15.8% a | 25.3% a |

| Single specialty group | 45.5% | 39.7% | 48.0% a | 46.2% | 46.7% | 43.8% |

| Multi-specialty group | 22.1% | 23.0% | 21.6% | 27.0% | 21.6% a | 20.3% a |

| Direct hospital employee | 5.6% | 5.7% | 5.6% | 9.3% | 6.3% b | 3.1% a |

| Faculty practice plan | 2.7% | 2.3% | 2.9% | 2.4% | 3.4% | 2.2% |

| Other 2 | 5.7% | 8.2% | 4.6% a | 5.2% | 6.3% | 5.3% |

| 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| N | 3466 | 976 | 2490 | 724 | 1747 | 995 |

Notes: 1For age, significance tests are shown relative to the under 40 category. ap<0.01 and bp<0.05. 2Other includes ambulatory surgical center, urgent care facility, HMO/MCO, medical school, and fill in responses.

Exhibit adapted from the American Medical Association (AMA) [1]. Employment data also indicates that the number of physicians working in practices owned by a hospital or integrated delivery system increased dramatically from 24% in 2004 to 49% in 2011, according to the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) Physician Compensation and Production Survey [4]. Physicians receive many benefits, such as negotiating leverage, profitability, lifestyle, and improved quality of patient care, in the group practice setting [5]. A study by Casalino and colleagues surveyed physicians regarding reasons as to why they either form or joined groups [5]. The authors of the study found that physicians cited gaining leverage with health plans as the main benefit of joining a group practice, while gaining economies of scale, especially for purchasing, management and information systems was the second benefit.3 Acquiring leverage with hospitals and profit from auxiliary services, predominantly operating outpatient diagnostic and surgery centers were cited as the third and fourth benefit, respectively [5]. Lifestyle, more specifically collegiality, calls and vacation coverage was cited next, and quality of patient care was cited the least. Physicians in this 2011 survey explained that the rewards for groups improving quality and coordinated care are scant, and inadequately valued or regarded [5].

A Brief History of Medical Group Practice

It is commonly considered that the medical group practice model originated in Rochester, Minnesota, home of the famed Mayo Clinic [6]. According to the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Mayo Clinic was founded in the late 1800s and had 386 physicians and dentists by 1929 [6]. It was by that time, a world-renowned integrated medical practice [6,7]. An article by Nelson discusses the origins of the private group practice, “The Mayo brothers were regarded as the ‘fathers’ of the group practice of medicine” [7]. Furthermore, “Dr. William J. Mayo recognized such distinction but said, ‘if we were we did not know it.’ The brothers established Mayo Clinic [with] no preconceived plan; rather, in a methodic manner, they resolved daily challenges of their rapidly growing surgical practice by surrounding themselves with internists, pathologists, […] and other specialized personnel whose expertise would enhance their surgical capabilities” [7]. The Mayo Clinic developed as a new type of private medical practice. The unique influence of the Mayo brothers was the integration of medical specialists into an efficiently working whole in private medicine [7]. Over time, Mayo-trained physicians increased across the country and some set up their own groups [6]. There were approximately 125 group practices in the United States by 1932, and almost a third of them were located in the Midwest [6]. According to Dr. Phillip Lee, a former Palo Alto Medical Clinic physician, “The number of practices was related to how close you were to Rochester. So their training played a huge role in preparing people to practice in a group setting” [6]. The growth of the group practice movement stemmed from increasing medical specialization, availability of new drugs, and growth in technology [6]. Thus, it was no longer possible for independent physicians to provide everything the patient needed for good health.6 Early leaders, such as the Mayo brothers, recognized that bringing in physicians from various disciplines together, along with new diagnostic services such as radiology and laboratory testing would provide better, comprehensive care.6 When the idea of group practice became momentous, not everyone agreed with the values and model of a group practice, as evidenced from some studies found in the literature. According to an article from 1972 by Metzner, group practices were increasing, “but not widely accepted at this point in time” [8]. Many groups, including the American Medical Association and local organizations were skeptical of physician groups [6]. Independent physicians disliked the proposition of multispecialty groups and did not believe that multispecialty groups provided better care [6]. Furthermore, many saw their business being threatened since groups could offer more consistent coverage on nights, weekends and holidays [6]. By the 1980s the group practice was becoming the preferred model of practice in the U.S. for most physicians. Today, the group practice model has been well established and proven to be the means to achieving economies of scale, improved purchasing power with vendors, and negotiation advantages with health plans and health systems. In 2011, physicians report gaining leverage with health plans as the main benefit of joining a group practice, while gaining economies of scale, especially for purchasing, management and information systems was the second benefit [5].

Methods: Literature Review Approach Study selection

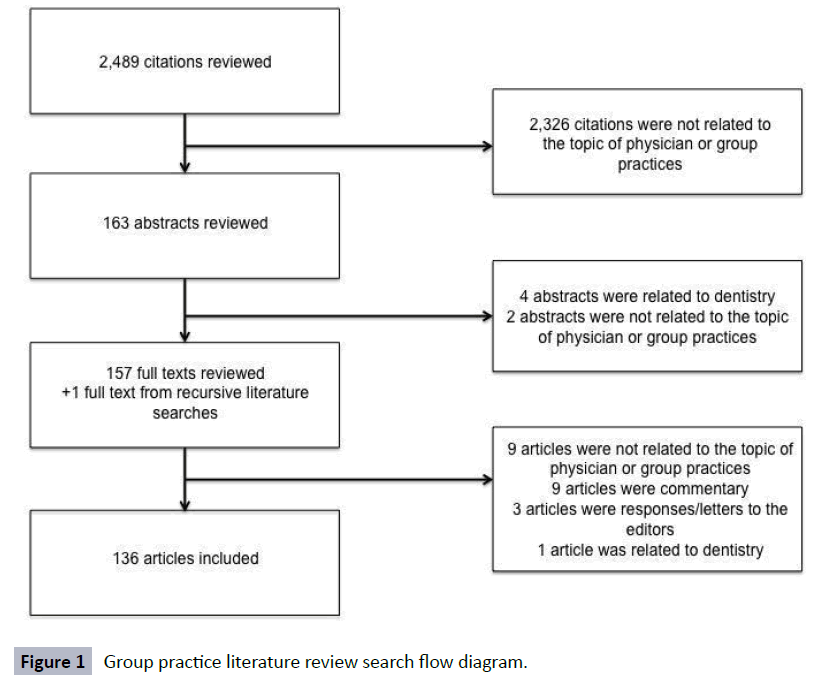

The peer-reviewed literature was searched on August 24th, 2015 via a computer search using the Ovid interface to Medline. We identified all relevant published articles that examined medical group practices, trends and size. Ovid Medline was searched from all years available, January 1st, 1947 through August 24th, 2015 with the following keyword combinations: [“group” or “group practice” or “physician” or “physician practice” or “practice”]. Given our emphasis on medical group practices, our search was limited to human studies published in English. The inclusion criteria were limited to studies related to the organization, behavior, or profiling of physician or group practices. Manual searches of references from relevant articles were performed to identify studies that were missed by our computer-assisted search. One investigator reviewed all publication titles of citations identified by the search strategy. Potentially relevant articles were also selected and selection criteria were applied. Articles were then manually and independently checked for inclusion criteria and disagreements were resolved through consensus with the second investigator. One investigator independently extracted required information from eligible studies using standardized forms. Data was collected on the title of the study, author(s), year of publication, journal, original versus review, the inclusion of a definition regarding group practice, whether the study addressed group practice trends or group practice size, the inclusion of a definition regarding a large group practice, whether the study was specific to anesthesiology or a different specialty in the hospital setting.

Results

Peer-Reviewed Literature Search

The search yielded 2,489 potentially relevant articles (Figure 1) based on the keywords. After initial review, 163 titles were potentially appropriate, and these abstracts were reviewed. 157 publications underwent full-text review. An additional publication was added from recursive literature searches to undergo full-text review. A total of 158 were entered into a chart and data on the title of the study, author(s), year of publication, journal, original versus review, the inclusion of a definition regarding group practice, whether the study addressed group practice trends or group practice size, the inclusion of a definition regarding a large group practice, whether the study was specific to anesthesiology or a different specialty in the hospital setting were extracted and organized. A total of 21 articles were excluded after examining the 158 articles. 9 articles were not specifically related to physician or group practice trends or size, 9 articles were commentary or personal accounts, 3 were responses or letters to the editors, and 1 article pertained to the field of dentistry. The remaining articles met all inclusion criteria, denoting a total of 136 studies.

Medical Group Practice Definition

Of the total 136 articles that met inclusion criteria, 24 provided a group practice definition. A majority of these 24 studies within the comprehensive literature review defined a group practice as, “Three or more physicians formally organized as a legal entity in which business, clinical, and administrative facilities are shared” [5,9-23]. This definition of a group practice has been the formal definition provided by the American Medical Association (AMA). A group practice is also defined as, “Three or more full-time physicians who pool their revenues and expenses from medical practice and redistribute income among members according to some prearranged plan” [24].

However, inconsistencies regarding the definition of a group practice still exist. Peyser and colleague instead define a group practice as, “at least four or more physicians practicing in a single or mixed specialty group” [25]. A recent study by Welch et al. used tax identification numbers to define medical groups “because all physicians using that number are part of the same financial organization” [26]. A study by Mehrotra and colleagues note that “their results also highlight the difficulty of defining a group” and define a physician group using existing definitions of a physician group determined by Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (MHQP) “as a distinct set of physicians that together contract with health plans and share resources and leadership (e.g. medical director)” [27]. One study also cited a vague definition, stating group practices are a “unique arrangement that is both a private group and public health clinic” [28]. The definition of a group practice has been defined and interpreted in numerous ways and an authoritative, legitimate definition is needed to help classify group practices.

Physician Group Practice Trends

Of the total 136 articles that met inclusion criteria, 32 referenced group practice trends. All 32 articles cite that group practices have increased over time, and will continue to steadily expand [5,8,11,14,17-20,22-24,27,29-42]. More specifically, it has been shown there is an increase in large group practices, and a decline in small group practices [26]. A study that assessed the benefits and barriers of large physician group practice by Casalino and colleagues found that “single specialty groups, mainly in 5 to 20 physicians were growing” [43]. In addition, Dove and colleague found that a higher proportion of physicians are members of a medical group and the average size of group practices is rising [33,44].

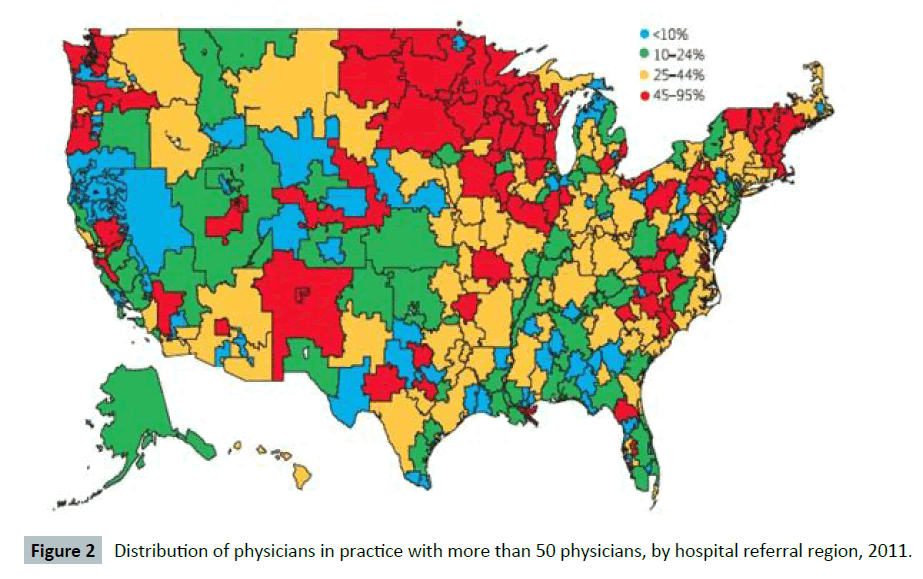

Kralewski et al. stated in 2004 that “The practice of medicine is nationally moving toward a group model” [34]. There are demographic and regional differences among group practices across the United States. A study by Welch and colleagues found that across all age groups, the proportion of physicians in large group practices increased from 2009 to 2011 [29]. Further, young physicians were less likely to be in solo practices compared to physicians who are older in the years 2009 and 2011 [29]. Between the years 2009 and 2011, the number of women in large practices increased , and were reported to be less likely in solo practices than men [26]. The Northwest, the upper Midwest, and Hospital Referral Regions in New England were more likely to have physicians in large practices in comparison to other regions [29]. Further, the Northeast, the Midwest, and the Southwest region saw the most prominent growth in large practices between the years 2009 and 2011 [29]. Exhibit adapted from the Welch et al. [29].

Classification of Physician Group Practice Size

There is still uncertainty regarding what is considered a small, medium, and large group. The American Medical Association stated, “it was not possible to compare estimates of practice size from the Physician Practice Benchmark Survey PPBS to those from the Physician Practice Information PPI survey.” and therefore size could not be established or profiled [1]. A study by Balfe also stated that, “the term ‘group practice’ covers a variety of meanings in regard to organizational arrangements, number of physicians and fields of practice required, and methods of distributing income and expense among members” [22]. Approximately 28% of 2014 physician survey respondents reported they belong to groups of 51 or more, however only 12% of physicians reported they were in a large group of this size, according to the American Medical Association’s Practice Benchmark Survey [4]. Conflictingly, the AMA has reported that only 4.6% of physicians were estimated to be in groups of 50 or more physicians (Figure 2), although this may be underestimated since hospital owned groups tend to be larger than physician owned groups [1]. Generally, physician survey respondents from The Physicians Foundation indicated they are in medium to large groups, in contrast to what numbers suggest from AMA [1,4]. Furthermore, responses to the 2014 survey are more recent, whilst AMA data is two years older [1,4]. Of the total 136 articles that met inclusion criteria, 30 referenced group practice sizes. However, only 11 articles in total explicitly provided classification for small, medium, and large sized groups. These classifications of group size differed significantly. Various definitions of what is considered a small, medium, large group from literature are listed below in Tables 2-4.

Table 2: Classification of a small group practice

| Article Title | Author, Year | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Workplace relational factorsand physicians' intention towithdraw from practice. | Masselink et al., 2008 | <10 physicians |

| Does affiliationof physician groups with oneanother produce higher qualityprimary care? | Friedberg et al., 2007 | 3-12 physicians |

| Structural characteristics ofmedical group practices | Kralewski et al., 1985 [36] | 3-5 physicians |

| Contempo '81. The changingstructure ofmedical group practice in theUnited States, 1969 to 1980 | Freshnock et al., 1981 [41] | <5 physicians |

| Organizational dimensions oflarge-scale group medical practice | Freidson et al., 1971 | 3-5 physicians |

| Physician practice size andvariations in treatments andoutcomes: evidence fromMedicare patients with AMI | Ketcham et al., 2007 [30] | 10-49 physicians |

| Structural characteristics ofmedical group practices | Kralewski et al., 1985 [36] | 6-10 physicians(multispecialty) |

Table 3: Classification of a medium or midsized group practice.

| Article Title | Author, Year | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Physician practice size andvariations in treatments andoutcomes: evidence fromMedicare patients with AMI | Ketcham et al., 2008 | 10-49 physicians |

| Structural characteristics ofmedical group practices | Kralewski et al., 1985 | 6-10 physicians(multispecialty) |

Table 4: Classification of a large group practice

| Article Title | Author, Year | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of physicians inlarge group practices continuedto grow in 2009-11 | Welch et al., 2013 [29] | >50 physicians |

| Workplace relational factorsand physicians' intention towithdraw from practice. | Masselink et al., 2008 | ≥10 physicians |

| Does affiliationof physician groups with oneanother produce higher qualityprimary care? | Friedberg et al., 2007 | 33-270 physicians |

| Benefits of and barriers to largemedical group practice in theUnited States | Casalino et al., 2003 [5] | >20 physicians |

| Structural characteristics of medical group practices | Kralewski et al., 1985 [39] | 16-25 physicians(multispecialty) |

| Why physicians choosedifferent typesof practice settings | Wolinsky, 1982 [16] | ≥8 physicians |

| A survey of group practice inthe United States, 1965 | Balfe, 1965 [22] | ≥25 physicians |

| Group practice in the UnitedStates | Pomrinse et al., 1961 [23] | ≥16 full-timephysicians |

A few studies found in the comprehensive literature review cited the Mayo Clinic, Palo Alto Medical Clinic, Scripps Clinic, Kaiser Permanente Medical Group, Leahy Clinic, and the Ochsner Clinic as examples of large specialty group practices [3,45]. Though, no specific classifications on the size of these large groups are given. There is considerable variation in the classifications of small, medium, and large group practice size. It is important to understand the classification of group practice size to prepare for future positioning in the market, as well as identify what is considered the “best size” for a specific practice. Factors to also consider may be demand for services, support personnel, office space, geographic location whether the practice is a managed care organization, and if the group is a hospital-based specialty. These factors, including group practice size may help in improving efficiency and quality outcomes.

Based on the results of this comprehensive review of literature, we recommend classifying group size as follows for future research on medical group practice trends:

Small Group Practice: Less than 10 Physicians

Medium Group Practice: 10 to 49 Physicians

Large Group practice: 50 or more Physicians

Future Research Direction and Next Steps

The next step in better understanding group practice trends is to explore predictors for group size, ownership trends and group acquisitions, and medical group consolidation trends. This future research will focus on anesthesiology group practices and rely on the theory of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and takeover strategy for other sectors and firms. Our efforts in defining and categorizing group practice size are an important step towards this future research. Firm (group) size is a key predictor variable in most M&A literature and hypothesis testing studies. The “Firm Size Hypothesis” proposes that smaller firms are likely to be acquired by larger firms [46-50]. Smaller group practices (firms) seem to have less transaction cost associated with being takeovers than larger groups practices (firms). Additional predictors of firm takeovers, mergers and acquisitions found in the theoretical literature that might need to be considered for this study of anesthesiology group practice are: inefficient group management, the mismatch between the group’s resources and its growth, the economic disturbance level for this sector (which seems to vary by region for medical group practices), and undervaluation (low market to book ratio). These factors, combined with industry/ sector specific predictor variables will help CHOT researchers design a prediction model for anesthesiology group consolidation activity and intensity.

Conclusion

Group practices in medicine have grown and changed significantly over the years in response to the progression of managed care and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010. Information is lacking on the recent trends of group practice and the classification of group size. Recommendations for further research include assessing whether variations in group practice, such as single-specialty or multispecialty groups or small, medium or large groups, are of value. In this comprehensive literature review, we identify the various definitions of a physician group practice, the recent group practice trends summarized from literature, as well as various classifications of group practice size. The results of this study also indicate that the number and size of group practices is expected to grow in the future.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. IIP-0832439. Any opinions,findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

References

- Kane CK, Emmons DW(2013) New Data on Physician Practice Arrangements: Private Practice Remains Strong Despite Shifts toward Hospital Employment. AMA23:1-16.

- Liebhaber A(2015) Physicians Moving to Mid-Sized, Single-Specialty Practices.

- The Physicians Foundation (2014) Survey of America’s Physician pp:1-72.

- MGMA (2013) Physician Compensation and Production 2013 Report.

- kCasalino LP, Devers KJ, Lake TK, Reed M, Stoddard JJ(2003) Benefits of and barriers to large medical group practice in the United States. Arch Intern Med 163:1958-1964.

- Foundation PAM (2015) A Brief History of Group Practice.

- Nelson C (1992) Origins of the private group practice of medicine. Mayo Clin Proc p:1.

- Metzner C, Bashshur R, Shannon G (1972) Differential public acceptance of group medical practice.Med Care10:279-287.

- LyDP, Glied SA (2013)The Impact of Managed Care on Physicians. J Gen Intern Med 26:109-114.

- O’Neill L, Kuder J (2005) Explaining variation in physician practice patterns and their propensities to recommend services. Med Care Res Rev62:339-357.

- Rossiter L (1984) Prospects for medical group practice under competition. Med Care 22: 84-92.

- Greene B (1996) Understanding the forces driving medical group practice activities an overview. J Ambul Care Manage19:1-3.

- Freshnock LJ(1980)The organization of physician services in solo and group medical practice. Med Care18:17-29.

- Goodman (1984) Comparative aspects of medical practice. Organizational setting and financial arrangementsin four delivery systems. Med Care 22:255-267.

- Roemer M, Mera JWS (1974)The ecology of group medical practice in the United States. Med Care 12:627-637.

- Wolinsky FD(1982) Why Physicians Choose Different Types of Practice Settings. Heal Serv Res17:397-419.

- Broske S, Lerner M (1971) Pediatric residents’ opinions on solo and group practice. J Med Educ 46:971-976.

- McNamara ME, Todd C(1969) A survey of group practice in the United States.Am J Public Health 60:1303-1313.

- Feldman LL(1970). Group practice development: a service of the Department of Health, New York City. Bull N Y Acad Med46:113-123.

- Lyon EK(1967) Will Group Practice Ease the Physician ’ s Work Load? Can Med Assoc Journal 97:1602-1605.

- Hunt G(1947) Medical group practice in the United States. N Engl J Med 237:71-77.

- Balfe B(1965)A survey of group practice in the United States .Public Health Rep 84:597-603.

- Pomrinse MGM(1961) Group practice in the United States. J Med Educ.

- Burns L(1996) Physicians and group practice- balancing autonomy with market reality. J Ambul Care Manage 19:1-15.

- Peyser N, Guzzetta D(1996) Physician Group Sizing. J Ambul Care Manage 19:34-49.

- Welch WP(1987) The New Structure of Individual Practice Associations.J Health Polit Policy Law12:723-739.

- Mehrotra A, Adams JL, Thomas JW, Mcglynn EA (2010)Cost Profiling in Health Care: Should the Focus be on Individual. Health Aff29:1532-1538.

- Mersha T(1985)The failure of the group model. HealthcManag 10:10-30.

- Welch WP, Cuellar AE, Stearns SC, Bindman AB(2013) Proportion of physicians in large group practices continued to grow in 2009-11. Health Aff32:1659-1666

- Ketcham JD, Baker LC, Macisaac D(2007) Physician Practice Size and Variations In Treatments and Outcome. Heal Aff26:195-205.

- Lin H-C, Xirasagar S, Laditka JN(2004) Patient perceptions of service quality in group versus solo practiceclinics. Int J Qual Health Care16:437-445.

- Rosenthal MB, Landon BE, Huskamp HA(2001)Managed Care And Market Power: Physician Organizations In Four Markets. Health Aff20:187-193.

- Dove HG,Greene BR(2000) Benchmarking medical group practices using claims data: methodological and practical problems. J Ambul Care Manage23:67-77.

- Kaissi A,Kralewski J, Curoe A, Dowd B, Silversmith J(2004) How Does the Culture of Medical Group Practices Influence the Types of Program used to assure quality of care? Health Care Manage 29:129-138.

- Kralewski J(1998)The organizational structure of medical group practices in a managed care environment. Health Care Manage 23:76-93.

- Robinson JC(1998) Consolidation of Medical Groups Into Physician Practice Management Organizations. JAMA279:144-149.

- De Sa J, Schrodel S(1996)Emerging state policy trends related to medical group practice-Alpha Center. J Ambul Care Manage 19:77-87.

- Blumstein L(1992)The changing private practice environment. J Ambul Care Manage 15:1-10.

- Kralewski JE, Pitt L, Shatin D(1985) Structural Characteristics of Medical Group Practices. AdmSci Q30:34-45.

- Korenchuk K, Hord J(1996) Managed care plans and the organizational arrangements with group practices. J Ambul Care Manage19:11-17.

- Freshnock LJ, Jensen LE(1981)Contempo ’81. The changing structure of medical group practice in the United States. JAMA245:2173-2176.

- Weinerman E(1969) Group practice revisited. Med Care 7:173-174.

- Casalino LP(2005) Disease management and the organization of physician practice. JAMA 293:485-488.

- Greene BR, Kralewski JE, Gans DN, Klinkel DI(2002)A comparison of the performance of hospital- and physician-owned medical group practices. J Ambul Care Manage25:26-36.

- Pauly MV(1996) Economics of Multispecialty Group Practice. J Ambul Care Manage19:26-33.

- Scurlock C, Dexter F, Reich DL, Galati M(2011) Needs assessment for business strategies of anesthesiology groups’ practices. AnesthAnalg113:170-174.

- Abouleish AE, et al. (2002)Comparing clinical productivity of anesthesiology groups. Anesthesiology 97:608-615.

- Kinyon GE(1960) Qualifications for the group anesthesiologist. AnesthAnalg39:537-541.

- Baird M, Daugherty L, Kumar KB AA(2015) Regional and Gender Differences and Trends in the Anesthesiologist Workforce. Anesthesiology5:997-1012.

- Simkowitz MA, Monroe RJ(1971) A Discriminant Analysis Function for Conglomerate Targets. South JBus:1-14.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences