Nurse Practitioners in Electroconvulsive Therapy

Hayley Paret1,2*, Paula Bolton2, Marie Borgella1 and Nadia Yang1

1Boston College, William F. Connell School of Nursing, Chestnut Hill, MA, USA

2Neurotherapeutics Program, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Hayley Paret

Doctor of Nursing Practice, Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner, Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) and Ketamine Provider, Neurotherapeutics Program, Belmont, USA

E-mail: hparet@mgb.org

Received date: February 24, 2025, Manuscript No. IPJHMM-25-20297; Editor assigned date: March 04, 2025, PreQC No. IPJHMM-25-20297 (PQ); Reviewed date: March 17, 2025, QC No. IPJHMM-25-20297; Revised date: March 24, 2025, Manuscript No. IPJHMM-25-20297 (R); Published date: March 31, 2025, DOI: 10.36648/2471-9781.10.1.393

Citation: Paret H, Bolton P, Borgella M, Yang N (2025) Nurse Practitioners in Electroconvulsive Therapy. J Hosp Med Manage Vol.10 No.1: 393.

Abstract

Background: All forms of neuromodulator, including Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT), are within the scope of practice for Psychiatric Nurse Practitioners (PMHNPs). Yet, most major payers do not consider PMHNPs billable providers, including Medicare (MCR).

Aims: The authors explored this issue through mixed methods and completed outreach to significant stakeholders to assess possible policy change. Methods: Methods included literature review, qualitative and quantitative research, creation of original policy materials, and engagement with key stakeholders.

Results: The literature review was supportive of ECT NPs but limited. Financial data from the single case study confirmed billing restrictions including “incident to” billing. Interview data supports ECT NPs but emphasizes limitations and related confusion and frustration. No change was made in CMS billing criteria language.

Conclusions: ECT NPs are an asset to this field. Yet, ongoing policy issues demonstrate a continued discrepancy between coverage and care.

Keywords

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT); Literature review; Nurse practitioners

Introduction

Nursing has been at the heart of neurotherapeutics since its inception [1-3]. Their role has evolved from supportive assistant to independent clinician [4-7]. There is a shortage of psychiatrists nationwide (HRSA, 2016) and an even further deficit of Electroconvulsive Physicians (ECT MDs). Only eighty-seven ECT MDs in thirty-two states of the US are practicing, according to the International Society for ECT and Neurostimulation (ISEN, 2024) listserv. However, approximately 14 million individuals suffer from severe and treatment-resistant mental illness (NIMH, 2023). The efficacy rate for ECT is 80-100% [8-12] yet the lack of care access to ECT MDs makes this treatment option impossible for many patients. To improve accessibility, many ECT teams now include NPs, who directly manage care, including treatment administration [13,14].

Practice regulations for NPs vary from state to state. According to the 244 Code of Massachusetts Regulations (CMR) 4.06 [15] and the American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA)’s latest Scope and Standards of Practice [16], ECT is within the scope of practice for NPs. ECT NPs and MDs receive the same training as recommended by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2001), which often includes specialized residency, training courses and certifications, fellowships, and rigorous on-site training with a skilled ECT clinician [17-21]. There is currently no standardized training or licensure (APA, 2001), which makes it challenging for clinicians to demonstrate competency.

Despite these points, NPs are currently excluded from MCR for reimbursement of ECT services. MCR CMS billing criteria states, “Code 90870 is limited to use by physicians (MD/DO) only” (2024). This language is not advised by the FDA or AMA. The FDA uses the following, “physicians and medical staff administering ECT” [22]. The AMA’s most recent CPT codebook (2023) states that “physician or other qualified healthcare professional” are eligible for psychiatry charge codes, including 90870. There is a significant discrepancy between the scope of practice and billing privileges, which limits care access to ECT in America.

Methods

Literature review

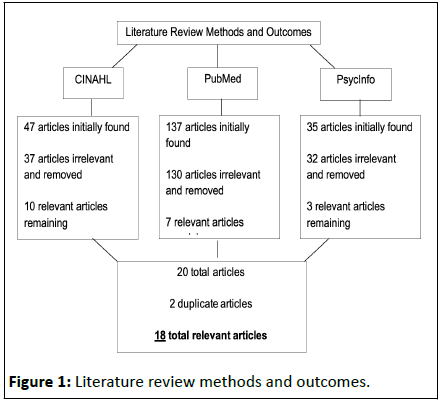

To better understand this problem, a literature review was conducted across multiple databases from May 2023 - March 2024. A limitation of publishing date prior to 2000, with preference of within the last five years, was set to encourage the latest evidence-based practice and data. Keywords included: (“nurse practitioner” or “np” or “advanced practice nurse” or “aprn” or “lead nurse” or “nurse-led” or “nurse-administered” or “nurse practitioner-administered”) AND (“electroconvulsive therapy” or “ECT” or “neuromodulation” or “neurotherapeutic” or “shock therapy” or “shock treatment”). Databases used were CINAHL, Pubmed, and PsychInfo. All keywords included the * symbol to include alternate forms of these words, such as “nurses” or “nursing.” It is important to note that this review did not target research articles with Nurse Practitioners (NPs) as authors on ECT-related topics, as it was not directly relevant to the focus. However, the omission of such works should be acknowledged, as they further demonstrate knowledge and competency as ECT providers. The methods can be found in Figure 1.

Qualitative research

Eight ECT NPs were interviewed in an unstructured format, with open-ended questions designed to elicit their experiences as ECT NPs. Recruitment among the sponsoring hospital and the APNA Neuromodulation Task Force was conducted from April 2023 until February 2024. Participants were interviewed on one to five occasions between May 2023 - March 2024. They were interviewed by video conference, phone, or in person. Content analysis and inductive coding were conducted based on the findings.

Case study

Financial data was collected from a single significant ECT NP at a local Massachusetts hospital, affiliated with the sponsoring hospital. Billing under their credentials, the reimbursement rate from MCR was examined with the assistance of the hospital’s finance department. The hospital’s financial team provided eighteen anonymized and randomly selected cases for assessment from April 2023. No clinical or private patient information data was reviewed.

IRB

This project was submitted for IRB determination through the sponsoring university’s IRB board, but the IRB review was deemed unnecessary [23].

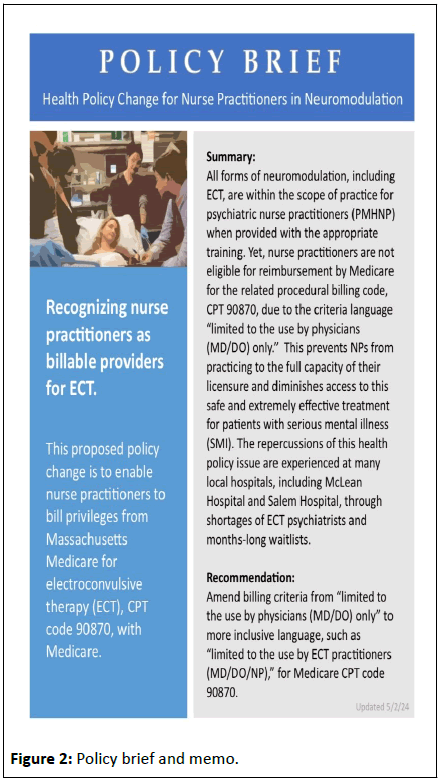

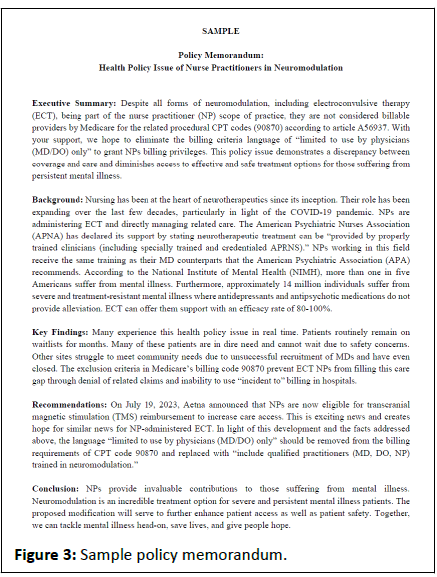

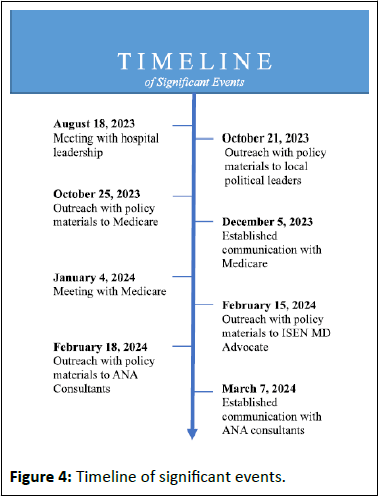

Significant events

Significant stakeholders were identified and engaged through formal meetings, presentations, and outreach efforts. These persons included leadership from sponsoring hospital, MCR, and local policy makers. Dedicated policy materials were developed including original Policy Brief and Memo. A timeline of these events and samples of materials can be seen in (Figures 2-4). To protect the privacy of all stakeholders involved in this work, identities will not be disclosed.

Results

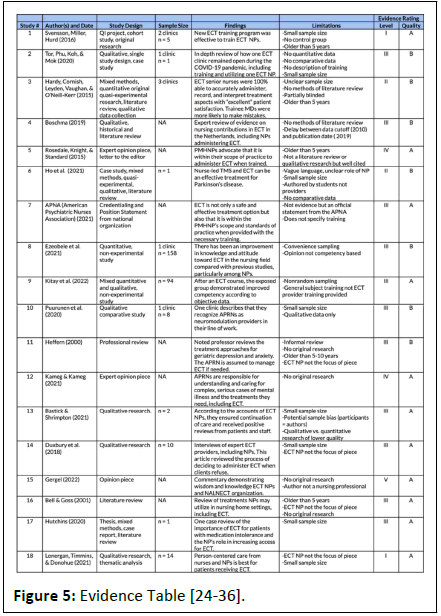

The results of the literature review were limited but overwhelmingly positive. Eighteen total articles were found of varying styles. Using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice Rating Scale (2005), the quality of the evidence was A-B. The type of evidence varied from I-IV; most were level III. Two articles were level I with small sample sizes. Both were original research, non-randomized controlled trials. The results demonstrate that nurse practitioners can safely and effectively provide ECT after completing the necessary training. Some articles directly supported ECT NPs. Others focused on other topics and offered passive support of the ECT NP, by mentioning this role as a secondary point or assumed position. See the complete evidence table in Figure 5.

In the case study, when billing under an ECT NP for the related 90870 CPT code, 100% of claims were denied by MCR for reimbursement. It is important to note that some ECT NPs bill under a supervising ECT MD with “incident to” billing but there are strict guidelines that limit this practice (WOCN, 2012; CMS, 2023). According to article A57065, incident to billing cannot be used in hospital settings. As ECT requires general anesthesia and many clients begin treatment while inpatient, most clinics are embedded into existing hospital systems. Furthermore, it is unclear if incident to billing is permissible for billing MCR for 90870. There is no mention of incident to billing in the 90870 code itself (CMS, 2024).

These findings validate the experiences of the ECT NPs interviewed. The themes unveiled included frustration and confusion with billing restrictions, inability to perform to the fullest extent of training and licensure, and stigma against ECT NPs. Yet, the most common theme was a passion for the field of neuromodulation. ECT is a life-saving treatment for those suffering from severe mental illness. ECT NPs want to increase care access to it. Support for ECT NPs is mixed among the ECT community but was secured by all key stakeholders in this piece. However, concrete progress in changing the MCR CPT code language has not yet been possible.

Conclusion

Whenever possible, nurse practitioners should serve as neurotherapeutic providers. This is not only because NPs should practice to the fullest extent of their licensure but also to improve care access to neuromodulation. There is a rising shortage of psychiatrists and neurotherapeutic providers worldwide. In recent times, ECT clinics have closed rather than turning to ECT NPs for assistance. Yet, in other parts of the world where these limitations do not exist, ECT NPs play a vital role in ECT care access. This was particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic when closures and shortages of ECT MDs were further exacerbated.

Additional research - particularly high-quality original research with a large sample size is necessary to further validate the credibility of ECT NPs and alleviate associated stigma. Having this data readily available to the neurotherapeutic community will be crucial. The full text of several of the articles listed above required special order by the sponsoring school’s library services as only abstracts were accessible to the general public (Boston College Libraries, 2024). Not everyone has the luxury of an institutional library at their fingertips. While this work focuses on Medicare (MCR), the challenges described above apply to other payors in the United States and internationally as well. Despite outreach to key stakeholders, no change to MCR billing criteria was accomplished during this project. By working together, we can strive to improve access to this safe and effective treatment for those suffering from persistent mental illness.

References

- (2023) American Medical Association (AMA). Medicine/Psychiatry, CPT Professional Codebook 2024. (1st Edition) : 759-760.

- (2021) American Psychiatric Association (APA). The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: Recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging. Washington, USA.

- (2021) American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA) (2021). APNA Position: Electroconvulsive Therapy. Neuromodulation Task Force Steering Committee. Virginia, USA.

- (2022) American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA). Psychiatric mental health nursing: Scope and standards of practice. (3rd Edition), Virginia, USA.

- Bastick L, Shrimpton T (2021) Reflections on advanced practice of nurse administered ECT as a treatment resource during the COVID-19 pandemic. Open Journal of Nursing, 11: 909-919.

- Bell M, Goss AJ (2001) Recognition, assessment and treatment of depression in geriatric nursing home residents. Clin excell nurse pract 5: 26-36.

- Blixen CE, Wilkinson LK (1994) Assessing and managing depression in the older adult: Implications for advanced practice nurses. Nurse Pract 19: 66-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- (2024) Boston College Libraries. Boston College Libraries Interlibrary Loan Service.

- (2023) Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS). Billing and coding: Outpatient psychiatry and psychology services.

- (2021) Commonwealth of Massachusetts Board of Registration in Nursing (MA BORN). Codes of Massachusetts Regulations: 244 CMR 4.00, section 4.06.

- Cortellini JF (2023) DNP program IRB determination request: NP eligibility for reimbursement for professional services rendered in connection with ECT, TMS, and other, comparable therapies.

- Dong M, Zhu X, Zheng W, Li X, Ng CH, et al. (2018) Electroconvulsive therapy for older adult patients with major depressive disorder: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychogeriatrics 18: 468-475.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Ezeobele IE, Ekwemalor CC, Pinjari OF, Boudouin GA, Rode SK, et al. (2022) Current knowledge and attitudes of psychiatric nurses toward electroconvulsive therapy. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 58: 1967-1972.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Gergel T (2022) RE: â??Shock tacticsâ??, ethics and fear: An academic and personal perspective on the case against electroconvulsive therapy. The British Journal of Psychiatry 221: 767-767.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Hardy S, Cornish J, Leyden J, Vaughan JJ, O'Neill-Kerr A (2015) Should nurses administer electroconvulsive therapy? J ECT 31: 207-208.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Heffern WA (2001) Psychopharmacological and electroconvulsive treatment of anxiety and depression in the elderly. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2000: 199-204.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Ho H, Jose I, Chessman M, Garrison C, Bishop K, et al. (2021) Depression and anxiety management in parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Nurs 53: 170-176.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Hutchins T (2020) Electroconvulsive therapy: A frontline treatment to consider. Nursing Capstones: 341.

- (2024) International Society for ECT and Neurostimulation (ISEN). Member Directory.

- Kameg BN, Kameg KM (2020) Treatmentâ?ÃÂresistant depression: An overview for psychiatric advanced practice nurses. Perspect Psychiatr Care 57: 689-694.

- Kitay BM, Walde T, Robertson D, Cohen T, Duvivier R, et al. (2022) Addressing electroconvulsive therapy knowledge gaps and stigmatized views among nursing students through a psychiatristâ??APRN didactic partnership. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 28: 225-234.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Luccarelli J, McCoy TH, Seiner SJ, Henry ME (2020) Maintenance ECT is associated with sustained improvement in depression symptoms without adverse cognitive effects in a retrospective cohort of 100 patients each receiving 50 or more ECT treatments. J Affect Disord 271: 109-114.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Lonergan A, Timmins F, Donohue G (2021) Mental health nurse experiences of delivering care to severely depressed adults receiving electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing 28: 309â??316.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- McDonald WM, Weiner RD, Fochtmann LJ, Vaughhn McCall W (2016) The FDA and ECT. Journal of ECT 32: 75-77.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- (2023) National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Mental Illness: Prevalence of Serious Mental Illness (SMI).

- Newhouse R, Dearholt S, Poe S, Pugh LC, White K (2005) The johns hopkins nursing evidence-based practice rating scale.

- Poole J, Dâ??Alessandro TM (2020) ECT: Dispelling the myths and focusing on facts. American Nursing Association: American Nurse.

- Puurunen A, Ikaheimo TM, Nissen M, Huotarinen A, Jyrkkanen HK, et al. (2020) A hybrid SWOT analysis of the neuromodulation process for chronic pain. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 16: 76-85.

- Rosedale M, Knight C, Standard J (2015) The role of the psychiatric mental health: Advanced practice registered nurse in the scope of psychiatric practice. J of ECT 31: 205-206.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Saglam NGU, Poyraz CA, Yalcin M, Balcioglu I (2020) ECT augmentation of antipsychotics in severely ill schizophrenia: A naturalistic, observational study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 24: 392-397.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Salani D, Goldin D, Valdes B, DeSantis J (2023) Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression: Dispelling the stigma. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 61: 11-17.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Sharma RK, Kulkarni G, Kumar CN, Arumugham SS, Sudhir V, et al. (2020) Antidepressant effects of ketamine and ECT: a pilot comparison. J Affect Disord 276: 260-266.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

- Svensson TK, Miller L, Hurd C (2016) Expanding the nurse practitioner role in treatment-resistant major depression. . J Hosp Med Manage 2: 1-4.

- Tor PC, Phu AHH, Koh DSH, Mok YM (2020) Electroconvulsive therapy in a time of coronavirus disease. J of ECT 36: 80-85.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Workforce National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (HRSA) (2016). National Center for Health Workforce Analysis: National projections of supply and demand for selected behavioral health practitioners (2013- 2025). Rockville, MA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- WOCN National Public Policy/Advocacy Committee (WOCN) (2012). Understanding medicare part B incident to billing: A fact sheet. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 39: S17-S20.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Indexed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences