Fraud and Abuse in U.S. Healthcare: An Evocative Appraisal

Anish Bhardwaj

Departments of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Neurobiology, John Sealy School of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), Galveston, Texas 77554, USA

Published Date: 2026-01-29Anish Bhardwaj*

Departments of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Neurobiology, John Sealy School of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), Galveston, Texas 77554, USA

- Corresponding Author:

- Anish Bhardwaj

Departments of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Neurobiology

John Sealy School of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB)

Galveston, Texas 77554, USA

E-mail: anbhardw@utmb.edu

Received: 31 December, 2025, Manuscript No. ipjhmm-26-21087; Editor Assigned: 02 January, 2026, PreQC No. P-21087; Reviewed: 16 January, 2026, QC No. Q-21087; Revised: 22 January, 2026, Manuscript No. R-21087; Published: 29 January, 2026, DOI: 10.36648/2471- 9781.12.1.422

Citation: Bhardwaj A (2026) Fraud and Abuse in U.S. Healthcare: An Evocative Appraisal. J Hosp Med Manage Vol 12 No. 1: 422.

Abstract

Fraud and abuse in U.S. Healthcare system are highly prevalent with colossal cost that accentuates significant burden and influences myriad stakeholders including healthcare providers, the public, patients and their families, healthcare facilities, third party payers and the U.S. government. It is estimated that three hundred billion dollars are lost annually on account of these unethical practices. Additionally, such healthcare malpractices compromise the cost-efficiency and quality of care delivery. Addressing medical fraud and abuse requires a multi-faceted approach blending prevention, detection and legal responses. This descriptive exposition underscores the importance of fraud and abuse in clinical practice, highlighting the key U.S. laws and statutes that are important for healthcare leaders, providers, trainees and administrators. The treatise underscores the necessity for policy makers and leadership in healthcare systems to invest in educating healthcare providers and administrators on laws, policies, compliance programs, adhering to best ethical practices and providing actionable insights toward developing targeted strategies in preventing and combating fraud and abuse.

Keywords

Healthcare fraud; Abuse; Detection; Prevention; Compliance

Introduction

Significance and scope of the problem

U.S. healthcare expenditure is approximately 18% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) amounting to $ 4.3 trillion annually [1]. Fraud and abuse in U.S. healthcare are highly prevalent and constitute a formidable challenge for myriad stakeholders including healthcare providers, the public, patients and their families, healthcare facilities, third party payers and the U.S. government [2-7]. Healthcare fraud can be described as the deliberate act of deceiving or misrepresenting information, with the awareness that such actions may lead to an unauthorized benefit for oneself or another individual [4-7].The term “abuse” is colloquially used to refer to acts that may not be illegal but characterized as “inconsistent or unsound practices (fiscal, business, or medical) and result in unnecessary cost to the reimbursement program for services that are not medically necessary or that fail to meet professionally recognized standards for healthcare” [5-8].

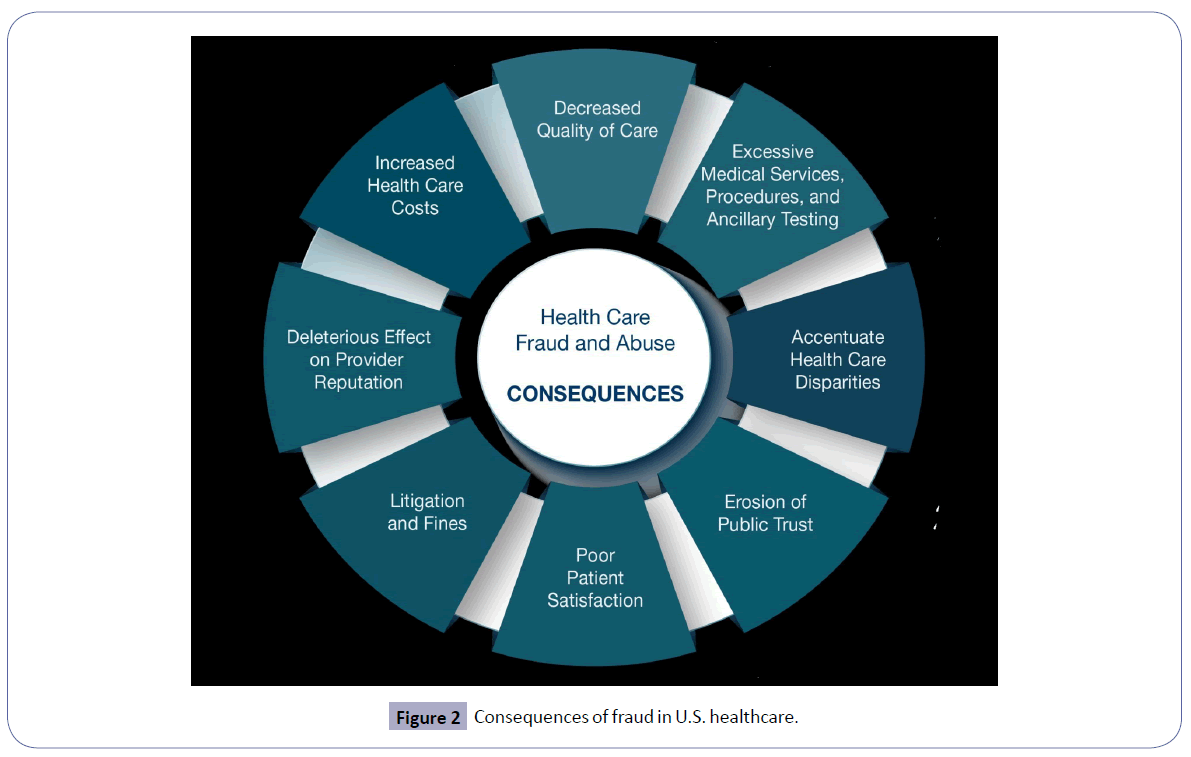

The National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association in the U.S. appraises the cost of fraud to the tune of over $300 billion annually, accounting for ~3%-15% of the total healthcare costs [6]. There is a plethora of common types of healthcare fraud [4]. These include billing for services that were never bestowed, “upcoding” that involves erroneous invoicing for other expensive services, performing medically needless services exclusively for generating third-party payer reimbursements (e.g., genetic testing, nerve conduction velocities), misrepresenting non-covered treatments as medically requisite treatments, misrepresenting patients’ diagnosis and medical records to justify tests and surgical procedures, unbundling (“fragmentation”; billing “piecemeal” for services that should have been invoiced together under a single comprehensive code, receiving kickbacks for patient referrals, relinquishing patient co-pays or deductibles for medical or dental care and over-billing the insurance company or benefit plan [4, 7]. In addition to the monetary corollaries toward exacerbating U.S. healthcare costs for the public, there are other far-reaching deleterious consequences of healthcare fraud and abuse including: 1) unnecessary excessive medical services, procedures and ancillary testing; 2) deleterious effect on healthcare disparities because fraudulent schemes often target and exploit vulnerable and medically underserved populations; and 3) erosion of public confidence in the U.S. healthcare system [4-8].

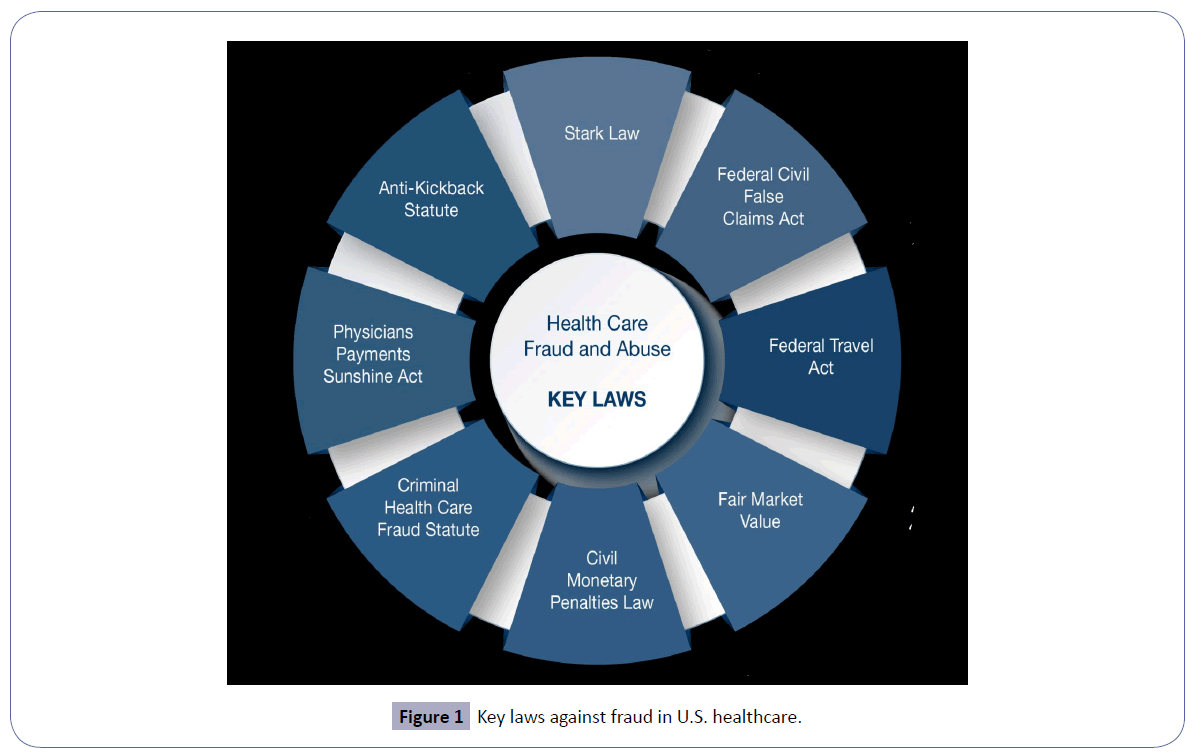

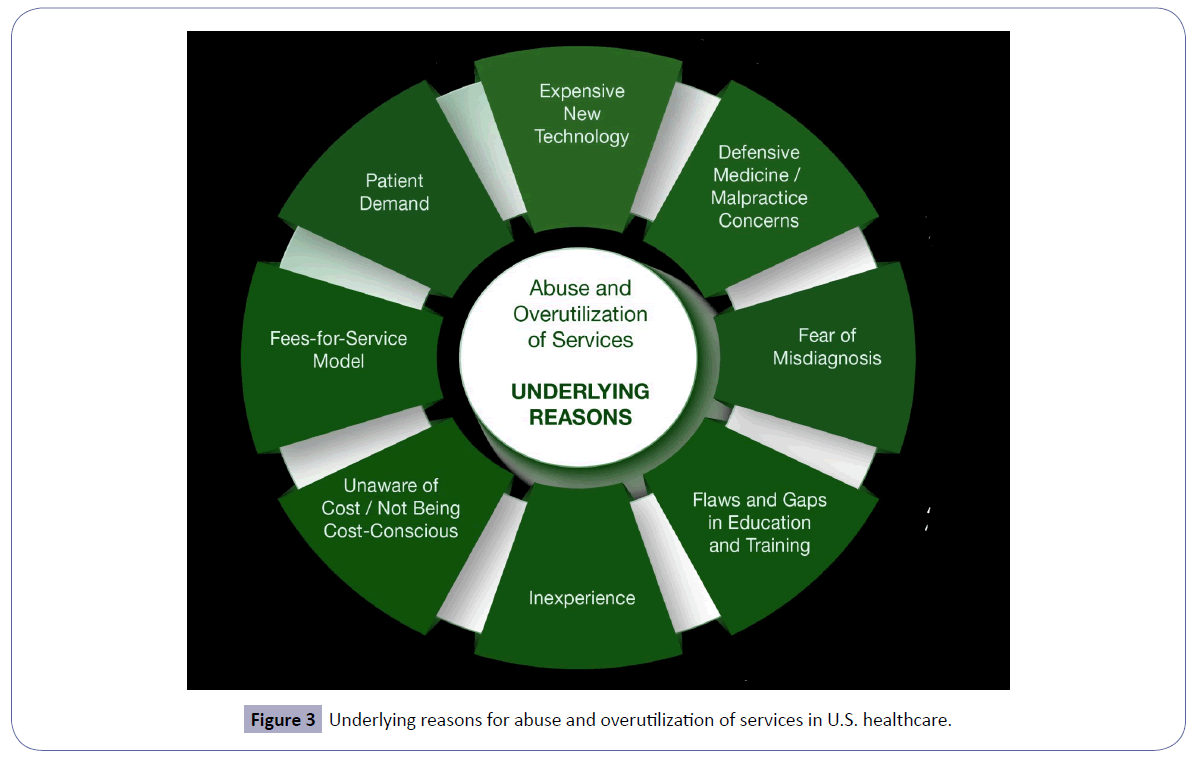

This treatise expounds on the existing common anti-fraud laws and statutes [9] in U.S. healthcare (Figure 1) and its consequences (Figure 2). It also enumerates the underlying reasons for abuse focused on overutilization of services and ancillary testing (Figure 3). Finally, this exposition underscores the critical importance of mitigation of fraud and abuse in U.S. healthcare through a multi-faceted approach.

The false claims act

The civil False Claims Act (FCA) was enacted on March 2, 1863, during the American Civil War under President Abraham Lincoln. The law was originally established to deter and recover financial losses resulting from widespread fraud by contractors who supplied substandard goods and services to the Union Army [10, 11]. Presently, the FCA is the primary statute used to prosecute healthcare fraud. In this context, the FCA prohibits the submission of false or fraudulent claims for payment to federal healthcare programs, including Medicare and Medicaid, regardless of whether there was a specific intent to defraud. The civil FCA defines “knowing” conduct broadly to include actual knowledge, deliberate ignorance, or reckless disregard for the truth or falsity of the information submitted [11]. Claims that arise from violations of the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) or the Stark Law (see below) may also be deemed false or fraudulent, thereby establishing liability under the FCA in addition to those statutes. The civil FCA also contains a whistleblower, or qui tam, provision that allows private individuals (e.g., current, or former employees, business partners, competitors, or patients) to bring lawsuits on behalf of the U.S. government and share in any financial recovery. Violations of the civil FCA may result in penalties of up to three times the government’s losses, plus civil fines of up to $11,000 per individual claim, with each Medicare or Medicaid service billed considered a separate claim [9-11]. In addition to civil enforcement, criminal penalties, including incarceration may apply for submitting false claims. The Office of Inspector General (OIG) may also impose civil monetary penalties for fraudulent or false claims [11, 12].

Anti-kickback statute

The Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) is a federal criminal law enacted as part of the Social Security Amendments of 1972 [2, 4, 5, 10, 11]. The law prohibits knowing and willful offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving of remuneration to induce or reward referrals or to generate business involving items or services payable by federal healthcare programs. Remuneration is broadly defined and includes anything of value, not limited to cash, such as free or discounted rent, luxury travel or accommodations, meals and excessive compensation for roles such as medical directorships or consulting arrangements [10, 11]. Unlike many other industries in which referral-based incentives are permissible, paying for referrals in federal healthcare programs is a criminal offense. The AKS applies to both parties involved in a kickback arrangement (individuals or entities offering or paying remuneration, as well as those soliciting or receiving it. Intent is a critical element in establishing liability under the statute [4, 5, 10, 11].

Violations of the AKS may result in significant criminal and administrative penalties, including fines, imprisonment and exclusion from participation in federal healthcare programs. In addition, under the Civil Monetary Penalties Law (CMPL) (see below) [13], physicians who offer or accept kickbacks may face civil penalties of up to $ 50,000 per violation, as well as assessments of up to three times the amount of remuneration involved. The statute includes regulatory safe harbors that protect certain payment arrangements and business practices, e.g., personal services agreements, space and equipment rentals, investments in ambulatory surgical centers and compensation paid to bona fide employees, provided that all conditions of the applicable safe harbor are fully satisfied [4, 5, 10-12].

Kickbacks in healthcare can result in overutilization of services, increased program costs, compromised clinical decision-making, patient steering and unfair competition [4, 5, 8]. The AKS prohibition applies broadly to all sources of referrals, including patients themselves. For example, while Medicare and Medicaid require beneficiaries to render copayments for covered services, routinely waving these copayments may imply AKS and should not be advertised [10, 11]. However, copayments may be made on a case-by-case basis when a physician determines that a patient is financially unable to pay or when reasonable collection efforts have been unsuccessful. It is also permissible to provide free or discounted services to uninsured patients [10-12].

In addition to the AKS, the beneficiary inducement statute imposes civil monetary penalties on physicians who offer remuneration to Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries to influence their selection of a provider or services [13]. Importantly, the U.S. government is not required to demonstrate patient harm or monetary loss to establish an AKS violation. A physician may be found liable even when the services provided were medically necessary and appropriately rendered. Likewise, accepting payments or gifts from pharmaceutical manufacturers, medical device companies, or durable medical equipment suppliers cannot be justified by the assertion that the physician would have prescribed the product or ordered the equipment regardless of the inducement [10, 11].

The stark law

The Stark Law, formally known as the Physician Self-Referral Law, restricts physicians from referring patients for Designated Health Services (DHS) reimbursable by Medicare or Medicaid to entities in which the physician or an immediate family member has a financial interest, unless a specific statutory or regulatory exception applies [4, 5]. Financial relationships under the law include both ownership and investment interests as well as compensation arrangements. For example, when a physician has an ownership stake in an imaging facility, referring patients to that facility is prohibited unless the relationship satisfies an applicable exception and the entity is barred from billing for services resulting from such referrals. Designated health services cover a broad array of medical services, including clinical laboratory testing; physical therapy, occupational therapy and outpatient speech-language pathology services; radiology and other imaging; radiation therapy and related supplies; durable medical equipment and supplies; parenteral and enteral nutrition and associated equipment; prosthetics, orthotics and related devices; home health services; outpatient prescription medications; and both inpatient and outpatient hospital services [4, 5, 10, 11]. The Stark Law operates as a strict liability statute, meaning violations can occur irrespective of intent or awareness [4, 5]. It also prohibits the submission, or facilitation of submission of claims stemming from prohibited referrals. Physicians found in violation may be subject to civil monetary penalties, required repayments and exclusion from participation in federal healthcare programs [4, 5, 10-12].

Civil monetary penalties law

The Civil Monetary Penalties Law (CMPL), codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a [13], authorizes the OIG to impose civil monetary penalties and, in certain cases, exclusion from participation in federal healthcare programs for a broad range of prohibited conduct. OIG is empowered to assess varying levels of penalties and assessments depending on the nature and severity of the violation, with penalties ranging from $10,000 to $50,000 per violation.

Examples of conduct that may trigger liability under the CMPL include: 1) submitting or causing the submission of a claim that the individual knows or should know is false, fraudulent, or for items or services not provided as claimed; 2) submitting a claim for items or services that the individual knows or should know are not payable by federal healthcare programs; 3) violations of the AKS; 4) violations of Medicare assignment requirements; 5) breaches of the Medicare physician participation agreement; 6) furnishing false or misleading information intended to influence decisions regarding patient discharge; 7) failing to provide an appropriate medical screening examination to patients who present to a hospital emergency department with an emergency medical condition or who are in labor; and 8) making false statements or misrepresentations on applications, enrollment forms, or contracts related to participation in federal healthcare programs [4, 5, 10-13].

Exclusion statute

The Exclusion Statute, codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7, requires the OIG to exclude individuals and entities from participation in all federal healthcare programs when they are convicted of certain criminal offenses [14]. Mandatory exclusion applies to convictions involving: 1) Medicare or Medicaid fraud, as well as other offenses related to the delivery of items or services under those programs; 2) patient abuse or neglect; 3) felony convictions for healthcare-related fraud, theft, or other financial misconduct; and 4) felony convictions for the unlawful manufacture, distribution, prescription, or dispensing of controlled substances. In addition to these mandatory grounds, the OIG has discretionary authority to exclude individuals and entities for other types of misconduct, including misdemeanor healthcare fraud offenses unrelated to Medicare or Medicaid, misdemeanor controlled substance violations, suspension or revocation of a healthcare license for reasons related to professional competence, performance, or financial integrity, the provision of unnecessary or substandard care, submission of false or fraudulent claims, participation in unlawful kickback arrangements and default on health education loan or scholarship obligations.

An individual or organization that is excluded from participation in federal healthcare programs is barred from receiving reimbursement from Medicare, Medicaid and other federal programs, including TRICARE and the Veterans Health Administration for any items or services they provide, order, or prescribe. Excluded physicians may not bill federal healthcare programs directly, nor may their services be billed indirectly through an employer, group practice, or other arrangement. Additionally, even when services are provided on a private-pay basis, any orders or prescriptions issued by an excluded provider are not eligible for reimbursement by federal healthcare programs [14, 15].

Healthcare providers are responsible for ensuring that they do not employ or contract with excluded individuals or entities in any capacity where federal healthcare program payment may be made for items or services furnished. This obligation requires screening of all current and prospective employees and contractors against OIG’s List of Excluded Individuals and Entities (LEIE), which is accessible through OIG’s Exclusions website [16]. Failure to comply with this requirement, by employing or contracting with an excluded individual or entity whose services are reimbursed by a federal healthcare program may result in civil monetary penalties and repayment of any amount attributable to those services [14, 15].

The physician payments sunshine act

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act (PPSA) is a federal transparency law designed to promote accountability and prevent conflicts of interest in healthcare. Enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, the law requires manufacturers of drugs, medical devices, biologicals and medical supplies that participate in federal healthcare programs to report certain financial relationships with physicians and teaching hospitals to the CMS [17]. Under the PPSA, reportable transfers of value include payments and benefits such as consulting fees, honoraria, research funding, meals, travel, gifts, ownership interests and royalties. CMS makes this information publicly available through the Open Payments database [18], allowing patients, researchers and regulators to review and evaluate financial interactions between industry and healthcare providers. The PPSA does not prohibit relationships between physicians and industry; rather, it emphasizes transparency so that patients can make informed decisions and policymakers can better monitor potential influences on medical decision-making. Failure to accurately report required information may result in significant civil monetary penalties for manufacturers. Overall, the PPSA plays a key role in strengthening public trust, encouraging ethical collaboration and enhancing integrity within the U.S. healthcare system [17].

Fair market value and other statutes

Fair Market Value (FMV) is a foundational concept in healthcare compliance, ensuring that compensation and financial arrangements reflect the value of services provided and are not influenced by the volume or value of referrals. FMV plays a critical role in fraud and abuse enforcement under statutes such as the Stark Law and the AKS, where excessive or inflated payments may signal improper inducements [4, 5, 10, 11]. In addition, the Eliminating Kickbacks in Recovery Act (EKRA) extends fraud and abuse prohibitions to substance use disorder treatment and laboratory services by criminalizing facilitating patient referral-based compensation, even in settings not covered by federal healthcare programs [19]. Together, FMV principles and EKRA reinforce safeguards against financial arrangements that could compromise clinical judgment, distort competition, or exploit vulnerable patient populations [20].

Federal travel act

The Federal Travel Act (FTA) [21, 22] was enacted in 1952 to give the federal government a means to combat organized crime. It is an important enforcement tool in addressing fraud and abuse in U.S. healthcare because it allows federal prosecutors to pursue individuals and entities that use interstate travel or communications to promote or conduct unlawful activities, including bribery and kickback schemes [22]. In the healthcare context, the FTA is often used in conjunction with statutes such as the AKS to reach misconduct that involves crossing state lines or using interstate facilities such as mail, telephone, or electronic communications. By incorporating violations of state bribery or commercial corruption laws, the FTA expands the government’s ability to prosecute complex, multi-state healthcare fraud schemes and reinforces accountability for improper financial arrangements that undermine patient trust and program integrity [21].

State statutes

State laws on healthcare fraud and abuse complement federal regulations by establishing additional standards and penalties for misconduct within their jurisdictions [23]. These laws often mirror federal statutes like the FCA, AKS and Stark Law but may include broader definitions of fraud, stricter reporting requirements and unique state-specific offenses. State authorities can pursue civil, criminal and administrative actions against providers, payers and entities that engage in fraudulent billing, kickbacks, patient abuse, or other forms of healthcare misconduct. Compliance with both federal and state laws is essential, as violations can lead to significant fines, exclusion from state and federal healthcare programs and reputational damage [23].

Proposed solutions for prevention and mitigation

Mitigation of fraud and abuse in U.S. healthcare is critical for myriad stakeholders (healthcare providers, the public, patients and their families, healthcare facilities, third party payers and the U.S. government). The focus is for policy makers and leadership in healthcare systems to invest in educating healthcare providers and administrators on laws, policies, compliance programs, adhering to best ethical practices and providing actionable insights toward developing targeted strategies in preventing and combating fraud and abuse [24]. Specifically, key elements should include: 1) disseminating knowledge to healthcare providers and administrators by leadership team of healthcare organizations; 2) cultivating an organizational culture with a committed leadership [25] for best ethical practices [26] and professionalism [27]; 3) building mandatory compliance programs; and 4) providing actionable insights and developing targeted strategies in combating fraud and abuse in a rapidly changing terrain of U.S. healthcare [24].

Compliance programs

Compliance programs for healthcare fraud and abuse are structured initiatives implemented by healthcare organizations to prevent, detect and respond to illegal or unethical conduct [28]. These programs are designed to ensure adherence to federal and state laws, including the FCA, AKS, CMPL, Stark Law and other regulations. Key components typically include written policies and procedures, ongoing employee training, designation of a Compliance Officer and Committee, regular auditing and monitoring of billing and clinical practices and mechanisms for reporting and investigating suspected violations, such as confidential hotlines. Effective compliance programs foster a culture of integrity, reduce the risk of fraud and abuse, minimize legal and financial penalties and enhance public trust in the organization’s delivery of care. Federal guidance, such as the OIG’s Compliance Program Guidance [29], provides a framework for developing and maintaining these programs, emphasizing initiative-taking risk assessment, oversight and enforcement [28].

Corporate integrity agreements

Corporate Integrity Agreements (CIAs) [30] are formal compliance agreements between the office of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) OIG and healthcare organizations that have been found to have engaged in fraud or abuse. Typically used as part of a settlement following investigations under the FCA, or other federal laws, CIAs require organizations to implement robust compliance programs to prevent future violations. Key provisions often include the establishment of a Compliance Officer and committee, mandatory employee training on fraud and abuse laws, regular auditing and monitoring of billing and clinical practices, reporting obligations to the OIG and retention of independent review organizations to assess compliance. CIAs are designed to promote transparency, accountability and ethical conduct, while allowing organizations to continue participating in federal healthcare programs, provided they meet the obligations outlined in the agreement. Noncompliance with a CIA can result in significant financial penalties or exclusion from federal healthcare programs [30].

Self-disclosure

The Self-Disclosure Protocol (SDP) [31] is a formal process established by the U.S. Department of HHS-OIG that allows healthcare providers to voluntarily report potential violations of federal healthcare program requirements, such as fraud or abuse, in exchange for a more favorable resolution. By participating in the SDP, organizations can disclose improper billing, overpayments, or other misconduct and cooperate with the government to investigate and resolve the issues. The protocol typically involves submitting a detailed report of misconduct, providing supporting documentation and working with OIG to determine appropriate repayment, corrective actions and, if applicable, civil, or administrative penalties. SDP encourages transparency and accountability, helps mitigate legal and financial risks and demonstrates a commitment to compliance and ethical conduct, often resulting in reduced penalties compared with cases discovered through government investigations [31].

Fraud and abuse in value-based healthcare

There is an ongoing paradigm shift from volume-based to Value-Based Healthcare (VBHC) that focuses on maximizing health outcomes relative to the cost of care delivered [32]. Fraud and abuse in VBHC present unique compliance challenges as payment models shift from volume to quality and outcomes [33]. While VBHC arrangements are designed to promote care coordination and cost efficiency, they can also create risks such as manipulation of quality metrics, inappropriate patient selection, improper financial incentives and misrepresentation of services or outcomes to increase reimbursement. Existing fraud and abuse laws (FCA, AKS and Stark Law) continue to apply, though regulators have introduced targeted exceptions and safe harbors to support legitimate value-based care. Effective oversight, accurate data reporting and strong compliance programs are essential to ensure that VBHC initiatives achieve their goals without compromising legal or ethical standards [32-35].

Conclusions and Future Directions

Healthcare fraud and abuse continue to pose significant and ongoing challenges within the U.S. healthcare system. Recent efforts to dismantle organizational silos and enhance coordination among HHS-OIG and other federal agencies, most notably through the establishment of a Health Care Fraud Data Fusion Center have strengthened enforcement capabilities. By uniting experts from the Department of Justice’s Criminal Division, Fraud Section, Health Care Fraud Unit Data Analytics Team and partner agencies and by leveraging cloud computing, artificial intelligence and advanced data analytics, these initiatives have proven highly effective. Nevertheless, evolving payment models, technological advancements and new care delivery approaches introduce emerging risks. Although federal and state statutes such as the FCA, AKS, CMPL and Stark Law provide a robust regulatory foundation, new forms of fraud continue to arise, particularly in VBHC, telehealth, digital health platforms and increasingly complex financial arrangements. Addressing these risks requires strong compliance programs, enhanced transparency initiatives such as the PPSA and initiative-taking monitoring of billing and referral practices. Most importantly, sustained collaboration among healthcare leaders, regulators, providers and industry stakeholders is essential to safeguard program integrity, protect patient safety and respond effectively to the rapidly evolving U.S. healthcare landscape.

Acknowledgement

None.

Data Availability Statement

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflict of Interest

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- AMA. Trends in Trends in Health Care Spending - Healthcare Costs in the US. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/874561066/Trends-in-Health-Care-Spending-Healthcare-Costs-in-the-US-AMA.

- Kalb PE (1999) Health care fraud and abuse. Jama 282: 1163-1168.

- Szewczyk T, Sinha MS, Gerling J, Zhang JK, Mercier P, et al. (2024) Health care fraud and abuse: Lessons from one of the largest scandals of the 21st century in the field of spine surgery. Ann Surg 5: e452.

- CMS. Common types of health care fraud. Fact Sheet. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/overviewfwacommonfraudtypesfactsheet072616pdf.

- CMS. Health care fraud and program integrity: An overview for providers. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/overviewfwaprovidersbooklet072616pdf.

- National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association (NHCAA). The challenge of health care fraud. Available from: https://www.nhcaa.org/tools-insights/about-health-care-fraud/the-challenge-of-health-care-fraud/.

- Hsiao WC. Fraud and abuse in healthcare claims. Available from: https://www.chhs.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Commissioner-William-Hsiao-Comments-on-Fraud-and-Abuse-in-Healthcare-Claims.pdf.

- Bhardwaj A (2019) Excessive ancillary testing by healthcare providers: Reasons and proposed solutions. J Hospital Med Management 5: 1-6.

- False Claims, 31 U.S.C. § 1347. Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2011-title31/pdf/USCODE-2011-title31-subtitleIII-chap37-subchapIII-sec3729.pdf

- Medicare fraud & abuse: Prevent, detect, report. CMS. Medicare learning network. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/fraud-abuse-mln4649244.pdf.

- Laws against Health Care Fraud. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/overviewfwalawsagainstfactsheet072616pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Office of Inspector General. Fraud & abuse laws. Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/physician-education/fraud-abuse-laws/.

- Legal Information Institute. 42 U.S. Code § 1320a-7a - Civil monetary penalties. Available from: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1320a-7a?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Office of Inspector General. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The Effect of exclusion from participation in federal health care programs. Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/exclusions/effects_of_exclusion.asp?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Office of Inspector General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Exclusion programs. Available from: https://www.oig.hhs.gov/exclusions/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Office of Inspector General. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Search the exclusion database. Available from: https://exclusions.oig.hhs.gov/.

- Legal Information Institute. 42 U.S. Code § 1320a-7h - Transparency reports and reporting of physician ownership or investment interests. Available from: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/1320a-7h?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. User guide for covered recipients. Open payments. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/open-payments-user-guide-covered recipients.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Eliminating Kickbacks. 18 U.S. CODE § 220 – Eliminating kickbacks in recovery act. Available from: https://www.thefederalcriminalattorneys.com/eliminating-kickbacks.

- Legal Information Institute. 18 U.S. Code § 220 - Illegal remunerations for referrals to recovery homes, clinical treatment facilities, and laboratories. Available from: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/220?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Legal Information Institute. 18 U.S. Code § 1952 - Interstate and foreign travel or transportation in aid of racketeering enterprises. Available from: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/1952?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Title 18 U.S. Code § 1952 – The travel act. Available from: https://www.thefederalcriminalattorneys.com/travel-act.

- FederalCharges.Com. Healthcare fraud charges & penalties by state. Available from: https://www.federalcharges.com/healthcare-fraud-laws/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Drabiak K, Wolfson J (2020) What should health care organizations do to reduce billing fraud and abuse?. AMA J Ethics 22: 221-231.

- Bhardwaj A (2022) Organizational culture and effective leadership in academic medical institutions. J Healthc Leadersh 25-30.

- Berdine G (2015) The hippocratic oath and principles of medical ethics. The Southwest RESPIRATORY and Critical Care Chronicles 3: 28-32.

- Bhardwaj Anish (2022) Medical professionalism in the provision of clinical care in healthcare organizations. J Healthc Leadersh 183-189.

- American Health Law Association. Managing fraud and abuse risks through effective compliance programs. Available from: https://www.americanhealthlaw.org/content-library/connections-magazine/article/47b0beec-5de8-4a30-a06c-50d0e233352d/Managing-Fraud-and-Abuse-Risks-Through-Effective-C

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2023) Office of Inspector General. General Compliance Program Guidance. Available from: https://oig.hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/HHS-OIG-GCPG-2023.pdf.

- Adler S (2024) What is an OIG corporate integrity agreement? The HIPAA Journal. Available from: https://www.hipaajournal.com/oig-corporate-integrity-agreement/.

- Self-Disclosure Protocol. Available from: https://oig.hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/self_disclosure_protocol_int.pdf.

- Khalil H, Ameen M, Davies C, Liu C (2025) Implementing value-based healthcare: A scoping review of key elements, outcomes and challenges for sustainable healthcare systems. Front Public Health 13:1514098.

- Lampert JG, Kendall D (2018) Clearing a regulatory path for value-based health care.

- Dyer O (2025) US government announces “largest healthcare fraud takedown in history”.

- US Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs (2025) National health care fraud takedown results in 324 defendants charged in connection with over $14.6 billion in alleged fraud.

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Google Scholar, Cross Ref, Indexed at

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences